He was still young when he married his sweetheart, Anne. And soon after that, he went down to London to make a name for himself. In a very short time he did exactly that. By the early 1590s he was well known as a poet and playwright, and a dramatic actor.

Quickly, too, he found favour at court. He befriended Henry Wriothesley (pronounced ‘Wrizzley’), the Earl of Southampton, to whom he dedicated two volumes of poetry. Southampton became Shakespeare’s patron. In a fascinating letter from the Bard to Southampton, Shakespeare said his gratitude for his patron’s support was a ‘Budde which Bllossommes Bllooms butte never dyes’.

He was a favourite, too, of Queen Elizabeth, who gave Shakespeare ‘a gold tissue toilet or table cover’, later exhibited with pride in a Stratford museum. Enjoying support such as this, Shakespeare assembled a personal library of a thousand books, a large number then as now.

Many of the books were Italian; many others were English poems and histories. We know this because Shakespeare produced a thorough catalogue of his library. He also signed many of his books, and wrote useful notes in the margins. In his copy of James the First’s book on Daemonologie, Shakespeare added a pithy and dismissive assessment: ‘Impossyble, WS.’

During Shakespeare’s life, many of his plays were published in slim, squarish ‘quarto’ editions. After his death, his friends and fellow actors, John Hemmings and Henry Condell, gathered the best verisons of his plays and published them just as he wanted, without adding anything and without making any other changes.

The resulting collected edition of Shakespeare’s works, the famous ‘First Folio’, went on sale in 1623. Today, almost four hundred years later, it is widely regarded as the greatest book in English, and perhaps the greatest literary work ever produced anywhere in the world.

OK, let’s back up a bit.

Truth be told, we’re not actually sure when Shakespeare was born. There is a record if him being baptised on April 26, but he was probably born a few days before that. The specific day is unknown. We also don’t really know if he poached deer, or if he went to his local grammar school, or any other school. The Stratford grammar school records for that time are lost.

His marriage, too, has documentary problems. On 27 November 1582, William Shaxpere was granted a licence to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton. The following day, a marriage bond was issued to William Shagspere and Anne Hathwey of Stratford. The Hathwey–Whateley difference is a puzzle. Are the two Annes the same person, or were two women involved, in some sort of intrigue? No one knows for sure.

The picture of Shakespeare at the royal court is also full of doubt. In Elizabethan and Jacobean times, writing plays was frowned upon, as was acting in them. Broadly speaking, players and playwrights were grouped in the same social category as highwaymen and pimps. Some of Shakespeare’s closest associates actually were pimps. George Wilkins, for example, was both a playwright and a brothel-keeper. Shakespeare’s arch rival, Robert Greene, had one foot in the theatre world and one in the underworld.

There’s scant evidence of Shakespeare ever having been a guest at court, and we can say with certainty that he never corresponded with Queen Elizabeth. And she didn’t give him any gifts. In the Earl of Southampton’s personal papers, there is no evidence he knew or supported Shakespeare. The letter expressing Shakespeare’s gratitude, ‘the Budde which Bllossommes’, is an eighteenth-century forgery.

The same person who faked that letter also fabricated Shakespeare’s library catalogue, and forged signatures and notes in books that Shakespeare supposedly owned. We actually don’t have any of Shakespeare’s personal books, or any manuscripts of his plays. (A small part of the manuscript of a play about Sir Thomas More is attributed to Shakespeare, but the attribution is contentious.)

People over the years have claimed to have found lost Shakespearean plays and other treasures. By and large, they were all hoaxes.

One thing is certain: many of Shakespeare’s plays were published in his lifetime. The first known edition of Shakespeare’s Hamlet appeared in 1603. The book is a mess.

In place of the famous soliloquy are these forgettable lines: ‘To be or not to be. I, there’s the point / To die to sleep, is that all? I all.’ Instead of, ‘O what a rogue and peasant slave am I!’, there is the colourful line, ‘Why what a dunghill idiot slave am I!’ (William Shakespeare’s father, John, was fined in Stratford for contributing to an illegal road-side dung-heap outside his home.)

In later editions of Hamlet, someone seems to have tidied things up and straightened things out. Just one example: the lines in the first edition, ‘But look, the morn in russet mantle clad, / Walks over yonder mountain top’, were corrected in later editions, because, it turns out, Denmark has no mountains.

Someone also added lines. Later editions of Hamlet are much longer than the first quarto. Those editions were probably intended for reading rather than performance. Which brings us to the famous First Folio.

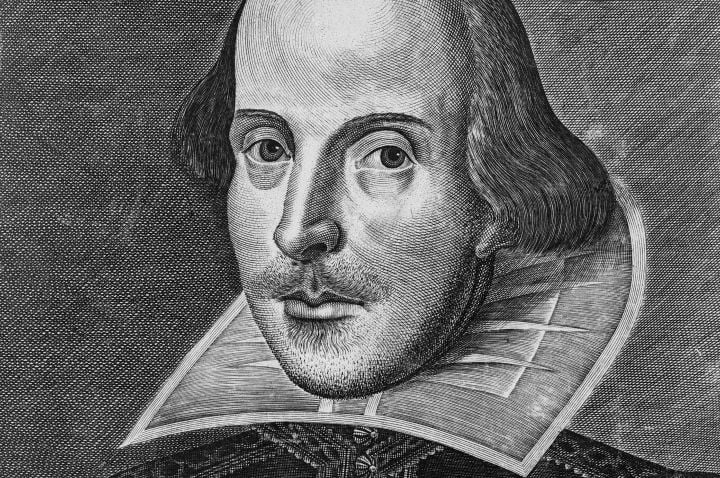

Published seven years after Shakespeare’s death, that book seems to have been edited and augmented by people who definitely weren’t Shakespeare. John Florio is probably one of those people, Ben Jonson another. Jonson provided a dedicatory poem for the First Folio, as well as some words to the effect that the title page portrait of Shakespeare is both a good and a bad likeness.

Jonson had already overseen another folio edition, the volume of his own collected works, published in 1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death. (In preparing his own works for publication, Jonson claimed to have removed the contributions of other playwrights. Shakespeare almost certainly did not do the same for the posthumous First Folio.)

What about Hemmings and Condell? The First Folio credits them as having preserved and compiled Shakespeare’s texts. But these two men were comedic actors, with no editorial experience, and their role was probably exaggerated as a way to confer authority on a book issued by a printer, William Jaggard, who was known for unscrupulous publishing of unauthorised works.

Apart from hidden editors, there were also hidden authors in the First Folio. Thomas Middleton, for example, collaborated on Timon of Athens and possibly All’s Well that Ends Well, but he isn’t credited in the Folio. Christopher Marlowe also had a role in the writing of some of Shakespeare’s history plays.

So what part did William Shakespeare perform in all this? Another William Jaggard publication provides an important clue.

In 1599, Jaggard wanted to release a volume of saucy verse. He gave the volume a saucy title, ‘The Passionate Pilgrim’, and put together twenty poems from various authors. Of the twenty poems, Shakespeare wrote five or so. But in a striking piece of marketing, Jaggard put Shakespeare’s name on the title page as the sole author.

Why? Because – with volumes of poetry such as Venus and Adonis and Lucretia, and with his privately circulating ‘Sonnets’ – Shakespeare had already established a firm reputation as an erotic poet.

He wasn’t well known in his lifetime, but to the extent that he had fans, many of them appreciated his writings as texts to use in ‘closet games’ and for ‘solitary pleasure’. Like his poetry, his plays are noteworthy for their bawdy content. At least in part, the First Folio was another attempt by Jaggard to profit from Shakespeare’s saucy brand.

Shakespeare may have had only a niche reputation in his lifetime, but the arrival of Romanticism in the eighteenth century gave him a big boost. David Garrick, the greatest actor of the era, embraced an even more edited version of Shakespeare, one with more happy endings and fewer rude bits.

That’s the version of Shakespeare who became a household name in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and he is the Shakespeare who is still influential today, via our subconscious judgements about his literary respectability and quality. Things, though, could’ve been very different. The Romantics might easily have embraced Jonson, or Middleton, or even Greene.

So when you’re watching a Shakespeare play, don’t feel bad if you think it is uneven or overlong. It’s OK to raise your eyebrows at the racy jokes and innuendo. And its OK to wonder, who was this Shakespeare person anyway?

PHOTO: Wikimedia Commons