Talk of Chinese “debt trap” diplomacy is nothing new, but a recent report by Harvard University researchers has resurrected long-held fears that China’s debt diplomacy poses a threat to Australian interests in the Pacific.

The crux of the report is that Pacific island states like Vanuatu and Tonga, as well as other nations in Southeast Asia, are at risk of undue influence from China due to unsustainable loans they’ve received for infrastructure projects.

The Australian Financial Review quoted the report as saying that while Papua New Guinea in particular has “historically been in Australia’s orbit”, it’s been “rapidly taking on Chinese loans it can’t afford to pay and offers a strategic location in addition to significant LNG and resource deposits” for China.

The story follows a well-trodden path from speculation to suspicion to alarm. Last month, another media report emerged saying China had approached Vanuatu about building a permanent military presence in the South Pacific – an assertion Vanuatu quickly shot down.

The latest report by the Harvard researchers comes with interesting context. A classified version of it was allegedly produced for the US Pacific Command last year, but the version leaked to the Australian Financial Review was written by graduate students, purportedly for the US State Department.

Interestingly, the students were supervised by Professor Graham Allison, who wrote the book Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?. The “Thucydides’s Trap” in the title relates to whether the US as a hegemonic power can accommodate China’s rise without resorting to war.

But this so-called trap does not necessarily point to historical inevitability. Therefore, a thorough analysis of the dynamics in the region is needed to fully understand China’s motivations, and what can be done to avoid conflict.

China has long been accused of using “chequebook diplomacy” to gain favour with nations around the world. The implication of the new “debt-book diplomacy” in the Harvard report is that China is using unsustainable loans to gain influence with Pacific island states that aren’t able to repay them.

Suffice it to say, this form of leveraging takes influence to a different level.

Historical fears

There is a long history of alarmism in Australia over the activities of strategic competitors in the Pacific. During the second world war, Japan was widely believed to have been poised to invade Australia from bases in the Pacific islands. This threat was later discredited, but the legacy of this fear of invasion from foreign powers lingers to this day.

During the height of the Cold War, Soviet fishing agreements with Pacific countries were also perceived to be a threat to Australian interests. These agreements were widely seen as strategic threats that could lead to military bases and/or spying arrangements, but nothing significant ever came from them.

The constant in Australia’s geostrategic view of the Pacific is that the region is viewed simultaneously as both a buffer and a potential location of threats.

In the second world war and the Cold War, perceived encroachments by strategic competitors led to a “strategy of denial”. This involved creating a buffer through forward defence initiatives, such as the Pacific Patrol Boat Program, in which Australia donated 22 vessels to Pacific island countries at the same time the Soviets were negotiating their “fishing agreements”.

It might not be a coincidence this program has been reinvented with a new Pacific Maritime Security Program that will see 21 vessels delivered to Pacific island nations from 2018-2021.

Reassessing Australia’s role

Australia has also been the largest aid donor to the Pacific region, a position that has withstood recent increases in Chinese aid. Furthermore, this development assistance to the region was prioritised in the latest federal budget.

This is significant considering the relative sizes of the two economies and the relative ease with which China can allocate resources (without transparency and without regard to a domestic constituency scrutinising its actions). Presumably, China could very easily overtake Australia as the largest donor if it wanted to, and the fact that it has chosen not to is telling.

It’s true China is becoming more active in the region. Australia appears to be responding through development assistance, defence cooperation and emergency disaster response with its Pacific neighbours, even if there is speculation the US doesn’t believe it’s doing enough.

But if there is a genuine Thucydides’s Trap in the Pacific, what’s needed is a coherent analysis of China’s interests in the region, rather than a quick and almost reflexive interpretation of their intentions as aggressive. (One angle worth exploring its China’s ongoing conflict with Taiwan over diplomatic recognition for the self-ruling island, as six of Taiwan’s 19 supporters are in the Pacific.)

Of equal importance for Australia would be to understand the motivations of Pacific island nations. What’s missing is any examination of why Pacific states might be welcoming China with open arms, or even whether they are simply begrudgingly welcoming them.

This opens a Pandora’s box. Could Australia’s (benign) neglect and perceptions of neo-colonialism actually be part of the problem? One that exists independently of China’s intentions?

This is certainly the case with [Australia’s sanctions against Fiji]from 2006-2014, which led to Fiji’s suspension from the Pacific Islands Forum and the creation of alternative forms of Pacific regional arrangements, such as the Pacific Islands Development Forum, which are supported by China.

Australia sees threats coming through the Pacific, and not from the Pacific, and this should be the foundation of its Pacific diplomacy. If Australia continues to reflexively see threats in China’s diplomatic moves in the Pacific, it may close off just the sort of creative diplomacy needed to escape a Thucydides’s Trap.

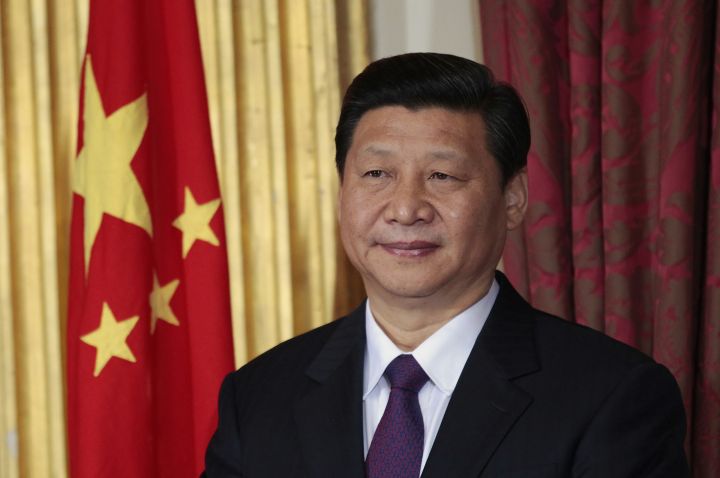

Photo: China President �Xi Jinping via Flickr

This piece originally appeared on The Conversation.