Since Vice President Mike Pence’s speech to the Hudson Institute in October 2018, American policymakers have increasingly used hardline rhetoric toward China. FBI director Christopher Wray described China as a “whole of society threat” in testimony to Congress.

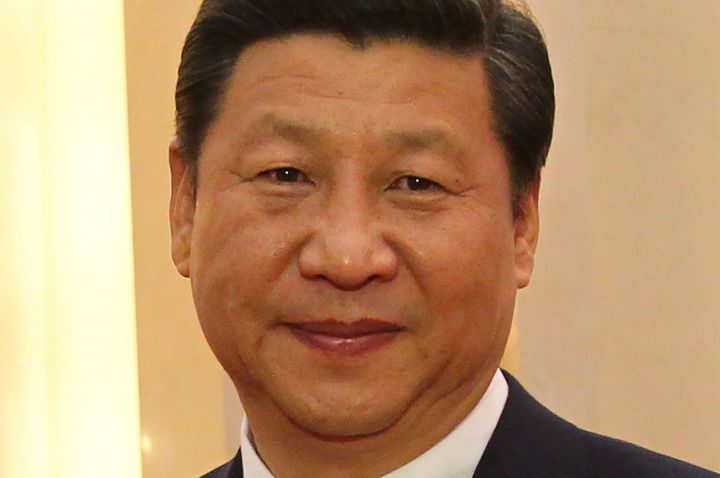

The view that China’s rise has come at the expense of the US is now seen as conventional wisdom. The evidently warm relationship established by leaders Donald Trump and Xi Jinping over chocolate cake at Mar-a-Lago in 2017 seems a world away.

Given this, it is unsurprising that many scholars and analysts have described the emergence of a new Cold War between China and the US (including myself in an essay last year).

The Cold War seems an obvious historical parallel. Like the former Soviet Union, China is also a communist country. And the US and China both have genuinely global interests and the capacity to act on those interests around the world.

But is the deteriorating state of US-China relations likely to tip the world back into the kind of ideological and geopolitical competition that dominated international politics for four decades after the second world war?

The Cold War’s unique dynamics

The Cold War was unlike any great power rivalry that has come before. Most obviously, it was the first geopolitical contest of the nuclear age. Both the US and Soviet Union rapidly developed vast arsenals of the most devastating weapons yet conceived. And their jockeying for power and influence meant that the threat of global annihilation was an ever-present risk.

But it was not just a contest for power – the Cold War was also fight between two evangelical ideologies. Each side believed their respective ideologies – liberal capitalism and Soviet communism – represented universal and fundamentally superior ways of organising society. The mobilisation of resources on a global scale, the nature of these commitments, and the risks they were willing to take was underpinned by the ideological dimensions of the contest.

The Cold War was principally focused on Europe and East Asia, yet it had a global reach. As colonial empires crumbled after 1945, the Soviets and Americans competed for influence among those fighting for their independence and the newly free. This indirect competition, which led at times to proxy wars, and its consequence of dividing the world into duelling blocs was the Cold War’s third main component.

…And a very different current world order

Sino-American relations are at their lowest point since at least 1989 and appear to be entering a level of mutual mistrust and suspicion not seen since the 1970s. Yet in spite of the trade war, explicit calls from US officials to treat China as a full-spectrum threat, and a growing militarisation of their interactions in the western Pacific, this is no Cold War.

More importantly, Sino-American relations are not even on that trajectory. And shrewd statecraft could easily avoid a repeat of the four decades when the world sat on the edge of nuclear apocalypse.

Presently, there is no meaningful ideological dimension to the competition between the two. While China is formally a communist state, its economy is an unusual mix of command, market and statist forms.

The country also shows little interest in spreading its particular mix of ideas and values globally, although, like all great powers, it is interested in increasing its global influence. China adheres to an orthodox view of sovereignty and evinces no meaningful desire to reshape the political and economic structures of states in its own image.

Equally, the contest between the world’s top two economies has not moved beyond the Asian theatre, geo-politically. Clearly, the US is concerned that Chinese technology may be used on a global scale to advance the country’s interests, hence its very visible campaign to try to contain Huawei’s global reach, but this is a long way from using conscripts to intervene in conflicts in Vietnam and Korea.

And most obviously, the economies of the USSR and US were hermetically sealed from one another. They may as well have been on different planets, such was the sparse nature of their interactions. The US and China could not be more different.

A rivalry for a new age

Today, China presents an increasingly confident face on the global stage. It is increasingly assertive and at times even abrasive in the way it tries to advance its interests.

But it is not yet explicitly contesting the US role in Asia or indeed the world. Rather, it is testing the US-led order to probe for vulnerability and creating new institutions to try to shape the world around it, like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt and Road Initiative.

But it is a long way from a direct confrontation. In part, this is because China’s risk appetite is not that great. But it’s also because Beijing believes it does not need to take such steps to increase its influence in the world.

For its part, the US has moved from its cautious engagement of China to a position in which it is trying to counter Chinese advances and contain its influence. Even with the tariff wars, the two remain profoundly economically interdependent and it will take many years for any real de-coupling of their relationship to occur.

The first great power rivalry of the 21st century has begun. It is not a re-run of the Cold War, however. Instead, this rivalry will look unlike any that has come before it. How acute the competition will be and the consequences for the world order will depend on the price China and the US are willing to pay to undermine and limit the other’s ambition.

PHOTO: Wikicommons

Originally published on The Conversation.