Is there another author whose reputation could ever rival Shakespeare’s? Certainly not from the 16th century, nor the 17th. Perhaps Johnson or Swift from the 18th? Austen or a Brontë from the 19th? Woolf, Joyce or Hemingway from the 20th? There are contenders, to be sure, but no one has put Shakespeare in the shade.

And yet there is a problem with Shakespeare.

Johnson, Austen, the Brontës, Woolf, Hemingway and Joyce all left behind evidence of their authorial lives. We can study diaries, letters, manuscripts, even juvenilia – a fulsome literary paper trail. With Shakespeare, though, the trail is meagre. Most of what we know of his life has come to us from arid official records, or via cryptic comments from contemporaries who hint at something mysterious or disreputable in the background.

What we notice most starkly is a documentary gap, one that people have attempted to fill in all manner of ways – by contacting Shakespeare through seances, or searching tombs and riverbeds for hidden manuscripts, or probing for secret messages in the plays, or positing all manner of “secret author” theories. According to those theories, William Shakespeare of Stratford was just a frontman for the true author of the Shakespeare oeuvre.

Many credible writers and scholars have embraced Shakespearean heresy. Disraeli, Emerson, Freud, William James, Mark Twain, Orson Welles and Walt Whitman all doubted Shakespearean authorship. Henry James was “haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practised on a patient world”.

The heretics are right to be sceptical. Apart from the documentary gaps, there are good reasons to doubt Shakespearean authorship of at least some of the plays. They were published by men with a track record of fraud, and the printed versions conceal much about how they were produced, including the role of collaborators.

Fundamentally, though, the heretics are wrong. Thanks to four centuries of scholarship, we know William Shakespeare was an author. And we know a great deal about what kind of author he was.

Gerard Langbaine’s Dramatick Poets includes this anecdote about Titus Andronicus:

…the Play was not originally Shakespear’s, but brought by a private Author to be acted, and [Shakespeare] only gave some Master touches to one or two of the principal Parts or Characters: afterwards he boasts his own pains; and says, That if the Reader compare the Old Play with his Copy, he will find that none in all that Author’s Works ever receiv’d greater Alterations, or Additions; the Language not only refined, but many scenes entirely new: Besides most of the principal Characters heightened, and the Plot much increased.

The first significant reference to Shakespeare as a dramatist – Robert Greene’s famous “Shake-scene” attack – is a complaint about him taking credit, as an “upstart crow”, for the writings of others. There is other evidence, too, that much of his work consisted of revising and retouching plays by other people.

What did it mean for a play to undergo the Shakespeare treatment? We know the answer to that, too. It seems a lot of the treatment involved sexing things up.

Lewd Venus

Today, William Shakespeare’s surname is utterly respectable. In the 16th century, however, the name had very different connotations. It was an old and earthy name, even a rustic one, akin to “Sheepshanks” and “Silcock” and “Wetherhogg”. His peers were always making fun of his provincial origins. People spoke of his “killcow conceit” – simultaneously an allusion to his father’s humble position in the Warwickshire leather trade, and a suggestion that Shakespeare’s cobbled-together plays were heavy with crude imagery.

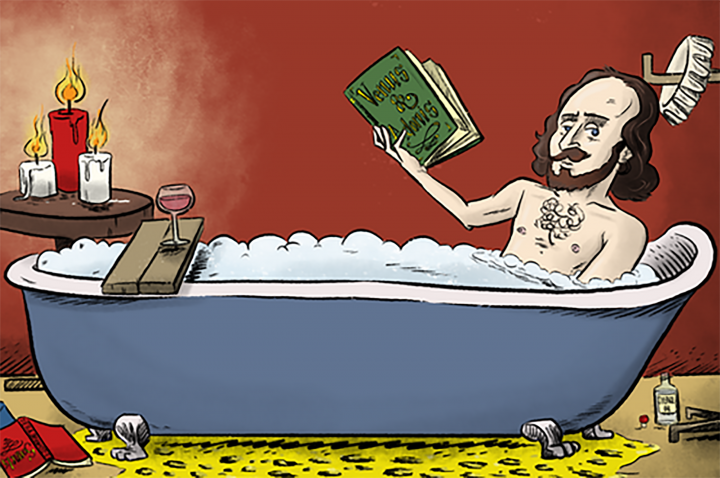

The name “Shakespeare” had another connotation as well. Shakespeare’s first reputation was as a poet, and particularly as a sex poet. In his three main books of poetry – Venus and Adonis, Lucrece, and the Sonnets – bawdy and erotic content is paramount.

Shakespeare made his first appearance in print with Venus and Adonis. Published in 1593, that book immediately earned a salacious reputation as an aid to what Michael Schoenfeldt called “solitary pleasure”. It is referred to in the anonymous Parnassus plays (1598–1602), in which the character Judico expresses love for the poem and its sweet, “hart throbbing” lines, and the character Gullio promises to “worship sweet Mr Shakespeare, and to honour him will lay his Venus and Adonis under my pillow”.

John Davies’ 1625 A Scourge for Paper Persecutors also mentions the poem, and suggests another way to enjoy it:

Making lewd Venus with eternall lines

To tye Adonis to her loves designes:

Fine wit is shown therein, but finer ’t were

If not attired in such bawdy geer:–

But be it as it will, the coyest dames

In private reade it for their closet-games.

Samuel Johnson would later list Venus and Adonis as one of the most scandalous and corrupting poems of the late 16th century.

He sex and she sex

William Shakespeare was very much alive above the ears and below the waist. A surprisingly high proportion of the documentary trail concerns his racy and bawdy exploits.

An important anecdote, from John Manningham’s 1601 diary, concerns a performance of the play we now call Richard III. Richard Burbage played the king and caught the attention of a beauty in the audience. The lady was so impressed by Burbage’s performance that she invited him to her home that evening — as long as he promised to stay in costume and character. Shakespeare got wind of the assignation and went first to the lady’s residence. Burbage arrived at the appointed time but Shakespeare was already inside, being “entertained and at his game”.

When the lovers were informed that Burbage was at the door, a triumphant Shakespeare sent his colleague a mischievous reply that contained a sharp lesson in English history. “William the Conqueror,” he said, “was before Richard the Third.”

Jane Davenant, mistress of the Crown Tavern in Oxford, is rumoured to have been another of Shakespeare’s lovers. Her son William, the future poet laureate, inferred on multiple occasions that Shakespeare was his father in more than just a poetical sense.

By the time Shakespeare’s Sonnets were published in 1609, they were somewhat old-fashioned and enjoyed little success. But an earlier manuscript version had circulated in the 1590s. According to the clergyman Francis Meres, Shakespeare’s “private friends” had devoured these “sugared sonnets” with relish.

Today, no copies of the Sonnets manuscript are known to exist. An enduring fantasy for bibliophiles and book-hunters, the manuscript is also a puzzle. The printed edition is a fascinating shandy of hetero- and homosexual flavours. Apart from being more raw and racy, the manuscript Sonnets may have been differently organised, perhaps into sections according to whose appetites were being served. The manuscript may also have included more prefatory matter – such as a letter from the author – that explained what he was up to.

Willy Shake-Spear

Printed versions of Shakespeare’s plays started appearing in the mid-1590s, but not until 1598 did they carry his name on their title pages. The men and women who bought these thin quarto editions knew exactly what to expect. They had already been conditioned by the outputs of William Shakespeare, sex poet.

Like those of his closest peers – men such as Greene and Christopher Marlowe – Shakespeare’s plays are noteworthy for their bawdy and disreputable content. Everyone knows the scene from Othello in which Desdemona and Othello make “the beast with two backs”. There are hundreds of comparable examples. In Hamlet, the prince and Ophelia trade spicy banter:

Hamlet: That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.

Ophelia: What is, my lord?

Hamlet: Nothing.

Falstaff’s speech in Henry IV Part 2 speaks of Justice Shallow in terms such as these:

…the whores called him mandrake: [he] came ever in the rearward of the fashion, and sung those tunes to the overscutched huswives that he heard the carmen whistle.

In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Adriano de Armado makes a striking confession about the king:

…it will please his grace, by the world, sometime to lean upon my poor shoulder, and with his royal finger, thus, dally with my excrement, with my mustachio; but, sweet heart, let that pass.

OK let’s not get too carried away: “excrement” probably meant “beard”, but the contact is still intimate.

Passages of this flavour are what Shakespeare’s contemporaries meant when they said he wrote in a raw manner, “from nature”. And they are what Thomas and Henrietta Bowdler removed to make their 19th century Family Shakespeare. (They excised, for example, the “beast with two backs”.) Johnson wasn’t far from the Bowdlers in his views about the raw parts of Shakespeare. “There are many passages mean, childish, and vulgar; and some which ought not to have been exhibited, as we are told they were, to a maiden Queen.”

Shakespeare’s Hamlet was probably more vital and bawdy than its predecessor version, possibly written by Thomas Kyd and now lost. Certainly Shakespeare’s King Lear is racier and more involving than the anonymously authored prior play, King Leir, which was registered in 1594.

The Bard had good reason to rev things up. Playwrights sometimes shared in the extra profits from the performance of successful plays. Writers were smart to add spicy content that would appeal to audiences from all classes.

Saucy sources

Apart from adapting earlier plays, Shakespeare took material from histories and poems and novels. His extensive use of sources shows there was no “secret author” behind the scenes who reliably fed him texts. His own library of sources performed that role.

Shakespeare’s personal collection of books and manuscripts has never been found, but one conception of it is compelling: an erotic library rich with imported Dutch and Italian smut along with English works such as Thomas Cutwode’s scandalous The Bumble-Bee (1599) and Giles Fletcher’s equally disreputable Licia, or Poemes of Love (1593).

The field of Shakespeare studies is all about mystery and discovery. There are many uncertainties about Shakespeare, but his achievement as a libidinous “sexer upper” allows us to put one precious stake in the ground.

Although sex is the unlikely key to understanding Shakespeare’s achievement as an author, for a long time the academy shunned his racy side. That side was not, however, wholly overlooked.

The New Zealand-born lexicographer Eric Partridge compiled the remarkable Shakespeare’s Bawdy (1947), which presents, among other things, scores of Shakespearean synonyms and euphemisms for vagina. Nothing Like the Sun (1964) by the novelist Anthony Burgess is “A Story of Shakespeare’s Love Life”; the covers of the Heinemann hardback and the 1966 Penguin softback show Shakespeare with his mistress, the mysterious “dark lady” of the sonnets.

Still, the Shakespeare of Partridge and Burgess is very different to the respectable, mainstream one. How did Shakespeare pull off the transformation from sex poet to literary monument?

Even in his lifetime he was shape-shifting, from boisterous lyricist and tearaway playwright to old-fashioned sonneteer and retired bookman. In the decade after his death, men tidied up his authorial legacy – and possibly added to it – but Shakespeare was still one writer among many, his reputation on a par with those of Marlowe and Middleton, and behind those of Jonson, Milton and Spenser.

But Shakespeare was tailor-made for the Romantic and Victorian eras, whose actors, scholars and hacks embraced and refashioned the Bard. Bowdlerising editors cut many of the ruder bits and added happier endings. By the 20th century, Shakespeare’s preeminence was immutable, his works as sublime and respectable as Beethoven’s symphonies or Mona Lisa’s smile. Things, though, could have been very different.

---

Professor Stuart Kells is the author of Shakespeare’s Library: Unlocking the Greatest Mystery in Literature (Text Publishing).

PHOTO: Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Originally published on The Conversation.