Neither a borrower nor a lender be,

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

– Hamlet Act 1, Scene 3.

In one of Shakespeare’s most oft-quoted passages Polonius is providing his son, Laertes, with some advice before he embarks for the bright lights of Paris.

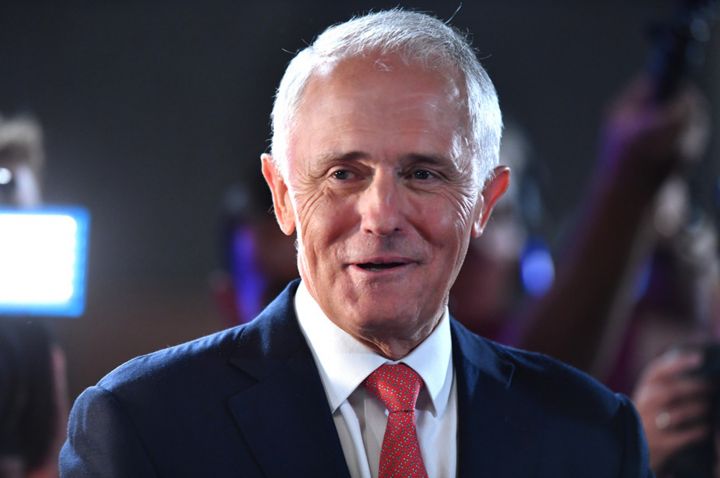

It might be a stretch to compare Turnbull and the hot-headed Laertes; he is more like Hamlet in his indecision, it might be said. But in a transactional space he has placed his government in an invidious position by outsourcing a domestic political conundrum.

Neither a borrower nor lender be …

The Trump administration may well honour an agreement struck with the previous Obama administration in its lame-duck phase to take up to 1,250 refugees from Nauru and Manus Island. But the question will remain: will the diplomatic aggravation and reputational damage to leader and country have been worth it?

Turnbull’s spokespeople have been assiduous in their efforts to persuade us that an Australian prime minister stood up to the bully in the White House, and that rather than suffering a humiliating rebuff he gave a good account of himself.

That may be true, as far as it goes. But the point is, we should never have been in a position in the first place where we were relying on America’s good graces to salve an Australian domestic political problem at a moment when an American election was being fought on the refugee issue.

Let’s repeat: a deal of questionable probity was struck with an outgoing American administration in contradiction with the policy impulses of an incoming replacement.

No purpose is served now by arguing that few expected Donald Trump to prevail. That is one argument you cannot take to the bank.

If there is a reasonable explanation for Trump’s behaviour towards a friend and ally it is that he is being asked to sanction an arrangement that is antagonistic towards policies on which he was elected.

Whoever dreamed up this slithery refugees-for-politics arrangement in the prime minister’s office, or that of the immigration minister or the foreign minister, should be held to account for placing Australia’s reputation in hoc to an administration untethered form normal diplomatic niceities.

This proposed refugees-for-politics transaction might be characterised as an attempted end run around various United Nations refugee conventions.

My colleague at The Conversation, Michelle Grattan, has suggested that Turnbull cut his losses, tell Trump the deal is off, and offer those incarcerated on Nauru and Manus a “one-off” amnesty to come to Australia.

If Labor had the guts it would support such a course. But its position is even less principled than that of the government, if that is possible.

Labor both criticises its implementation and runs dead on such a transaction at the same time. This puts it in the position, discreditably, of both borrower and lender in this argument.

None of this is to suggest border controls be loosened, or that measures in place to counter unauthorised arrivals be relaxed. It is simply an argument to deal with an existing problem that has caused enormous rancour in Australia, and one that could be resolved if separated from politics.

Unfortunately, and in the case of a government bereft of an appealing political narrative, the “stop the boats” refugee mantra provides a port in a storm, it might be observed.

This brings us to the broader question of how countries like Australia might deal with a White House like no other in living memory.

If it is any comfort to Turnbull in his mendicant state as far as the refugee deal is concerned, leaders of comparable countries like Canada are faced with the same dilemma, and it is this. To what extent does Turnbull, or Justin Trudeau of Canada, or Angela Merkel of Germany, or Theresa May of Britain, assert their country’s values and at the same time criticise Trump at a moment when America’s own values are being trashed?

Trudeau perhaps provides the better model for an Australian prime minister seeking guidance about how to deal with the Trump phenomenon. Inside and outside the Canadian parliament, Trudeau has avoided direct criticism of the Trump administration, but he has made his views known via social media.

No such public sentiments have emanated from an Australian prime minister hostage to his party’s unsentimental refugee policy, and a supplicant on the issue to a new American administration.

For her part, Merkel did not dissemble, as might be expected, and in contrast to others, including Turnbull. Her spokesman said:

The chancellor regrets the US government’s entry ban against refugees and citizens of certain countries. She is convinced that the necessary decisive battle against terrorism does not justify a general suspicion against people of a certain origin and a certain religion.

Finally, a word about the Battle of Hamel, of July 4, 1918. In the welter of words written about the Trump-Turnbull contretemps, in which an American president allegedly hung up on an Australian prime minister, much has been made of Australia having been America’s most steadfast ally from the first world war on.

It is true that American troops served alongside Australians under the command of then Lieutenant General John Monash. But it is also the case America’s commander, General John J. Pershing, whittled back American involvement on the ground for operational reasons.

In the end, a relatively small number of American soldiers were involved in what proved to be a successful operation in efforts to defeat the German army on the River Somme.

Like the reduced American commitment at Hamel, a Trump administration may seek to minimise its intake of refugees in what has proved to be an exercise in Australian diplomacy that has brought little credit to those involved.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Photo: AAP/Mick Tsikas.