The congress is held every five years and is a symbolic event, rolling out new leadership in the party. The real politicking occurs in the months leading up to the autumn jamboree.

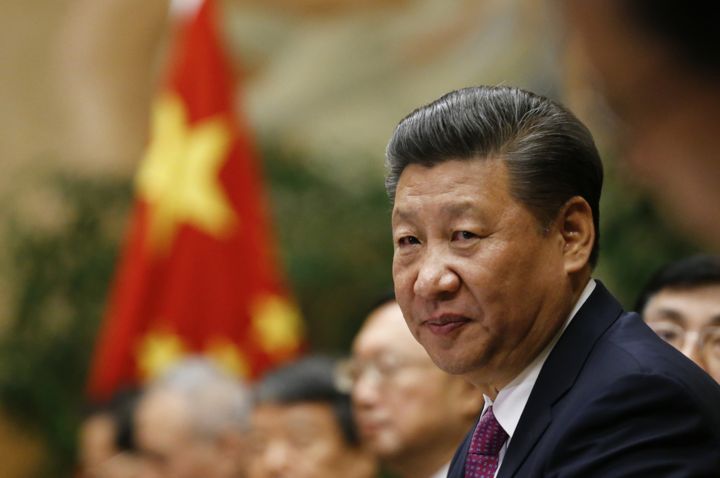

While Xi Jinping will no doubt continue as general secretary of the party, the question is whether he will be able to install enough people loyal to him in the key decision-making bodies. Although regarded by many as the most powerful party leader since Deng, in reality Xi cannot call on a majority of loyalists in either the Politburo Standing Committee, or the larger Politburo. In 2017, Chinese politics will be fixated on these issues and whether or not Xi is able to craft a party elite subservient to him.

One major challenge for Xi will be managing this manoeuvring while being subject to what is likely to be a more muscular American policy in Asia. The Trump administration plainly views China as a challenge to American interests and power.

The US will put pressure on China in 2017, and it seems increasingly probable that this will relate to China’s maritime disputes. US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson flagged China’s actions in the South China Sea as especially problematic during his confirmation hearings. However it occurs, China will faced a dilemma about how to respond to a more aggressive US.

Beyond these two major issues, big questions about the Chinese economy linger. Can the party undertake the 300 reforms flagged by Xi? Do its banks have structural problems? And is a financial crisis over the horizon? This year may provide answers to these important issues.

One of the earliest tests, of course, will come with the election of a new chief executive of Hong Kong at the end of March. The process began last year and caused considerable tensions in the Special Administrative Zone. It has the potential to be exactly the kind of high-profile headache the party would hope to avoid in a party congress year.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Photo: REUTERS/Denis Balibouse