The summit will be the highest profile activity to date of the Belt and Road Initiative, a program that has become central to China’s international engagement and a core priority of President Xi Jinping. Previously branded abroad as the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative - a direct translation of its Chinese name - it is a wildly ambitious program to link China more effectively with its trade partners in Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

It is the most important part of Chinese foreign policy. It has more than a 1.5 trillion USD earmarked from various sources, such as the China Development Bank, to fund infrastructure projects associated with the initiative. Yet it has scarcely been noticed in Australia. Shadow Foreign Minister Penny Wong recently penned an op ed arguing for Australian engagement with the initiative - so far this is the only substantive contribution made by a senior political figure.

Around a year into his term in office, President Xi Jinping gave two speeches setting the program in train. The first, in Kazakhstan in September 2013, proposed building a new ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ to connect western China to central Asia, the Middle East and Europe. On 29 April, a train laden with 30 freight carriages pulled into Yiwu in China’s east, having set off from London 18 days previously. This was the first of what the government hopes will be a significant increase in the movement of goods and commodities in and out of China by land.

The second speech, to the Indonesian parliament, announced plans for a Maritime Silk Road, a sea-based complement to the land based program to drive economic connectivity between East and West.

While both speeches were notable at the time, observers thought the lack of detail, the vast scale of the program and the fraught politics of building the kind of infrastructure needed to move goods from western China to Europe, pump oil from Pakistan to Xinjiang or deliver gas from Burma to Kunming seemed unrealistic, to say the least.

Some dismissed the initiative as an ambitious thought-bubble, while others saw a geopolitical gambit to advance Chinese influence in Eurasia, prompted by Obama’s pivot to Asia. But even these more hawkish views did not take the idea especially seriously because of China’s track record of cack- handed diplomacy, its lack of strategic capacity and again its nebulousness.

But in the intervening years, China has established a Silk Road Fund, set aside significant other development funds and, crucially, made the Initiative a fundamental priority in the country’s policy settings. Indeed, there is a sense within China that any program that any government wants to advance has to be framed in terms of the Belt and Road Initiative.

China sees the move as a means to improve economic development in the country’s west and south, both much more deprived than the dynamic coastal provinces. China is trying to move to a more consumer and service oriented economic model and much of the industrial capacity built up over recent years will be redundant. The initiative provides the opportunity to export this excess capacity and capital reserves.

It would also give China multiple economic channels to move goods in and out of the country, whether that is oil from the Middle East, commodities from Africa, or consumer durables bound for Western Europe. At present pretty much everything moves in and out of China via the country’s megaports on the Eastern seaboard. This concentrates activity on the east and also makes the country vulnerable to maritime threats. Connectivity that bypasses the Straits of Malacca overland or by sea diversifies threats and improves economic opportunity.

China also sees the economic benefits that will accrue to countries in Central Asia, the Indian Ocean Region and India and from which it will benefit. Equally, the initiative would increase its political capital and through boosting trade ties will also align Eurasian countries’ interests with Beijing’s.

One should not underestimate the scale of the challenge China faces in realising its Belt and Road ambition. The train trip from London involved many changes of rail carriage as there is no single gauge on the line. Equally building gas or oil pipelines through Pakistan or Burma will be as challenging in engineering terms as it will be politically fraught. And capital in China presently sees more risk than reward in many of these markets.

Nonetheless, if there is a country that can pull off such ambition it is the People’s Republic of China. More importantly, even if they only achieve half of what they seek it will still have a revolutionary effect.

China’s position at the heart of a Asian-centred world economy will be secured. It will increase its geopolitical advantage over the US, improve its economic welfare and strengthen its diplomatic leverage globally. Equally, it presents China with the chance to provide economic leadership to a world crying out for it, at a time when its erstwhile leader and model lack both appetite and appeal. The downside, for Australia is that it will reduce US influence and further erode the liberal international order.

It is far from clear whether Beijing’s ambitions for the Belt and Road Initiative will be realised. Potential partners may not buy into China’s vision. And if the Chinese economy suffers a downturn of the kind some expect, then its capacity to pay for the initiative would be questioned. However it plays out, make no mistake that China has very significant ambitions that must be taken seriously. Twenty-eight world leaders are taking time out of their busy schedules to do just that. Australia should too.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

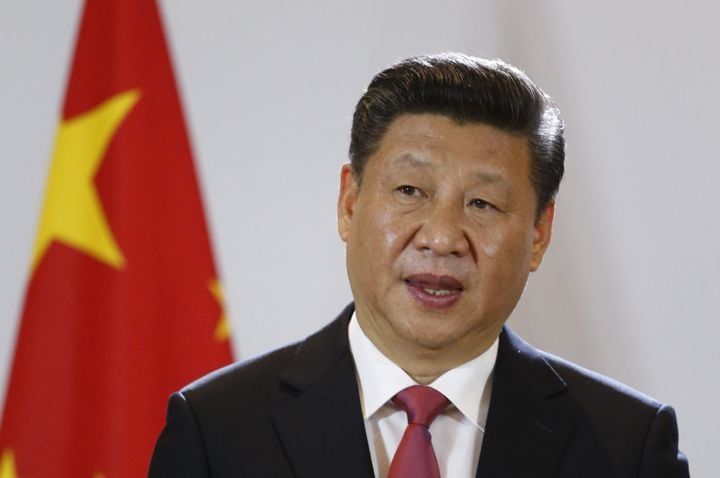

Photo: Reuters/Denis Balibouse